Lower bound on the number of rounds in crash stop synchronous consensus

Any consensus algorithm with \(f + 2 \leq n\) processes that tolerates \(f\) crashes requires more than \(f\) rounds.

We suppose binary consensus in a synchronous model where each round consists of a message sending and message delivery phase. Each non crashed process must agree on a value in \(\lbrace 0, 1 \rbrace \).

Here is an informal reasoning and description of the ‘chain argument’. The full proof is in Impossibility Results for Distributed Computing.

Structure

First, we reason that there in an initial state with two executions \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\) such that the consensus leads to a different result. In \(\alpha\) exactly one process crashes at the beginning of the first round. In \(\gamma\) no processes crash.

Then, we will argue for any \(f\) round execution with \(f + 2 \leq n\) processes, that any execution is equivalent to one without crashes. This result combined with the first gives us the desired lower bound.

We’ll use ‘chain argument’s. A chain argument constructs a sequence (chain) of executions \(\alpha_0, \alpha_1, …, \alpha_k\) such that every adjacent pair is indistinguishable by at least one correct process. This means that each execution must return the same result.

a) The same configuration can lead to different results

Statement 1: There in an initial state with two executions \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\) such that the consensus leads to a different result. In \(\alpha\) exactly one process crashes at the beginning of the first round. In \(\gamma\) no processes crash. Why?

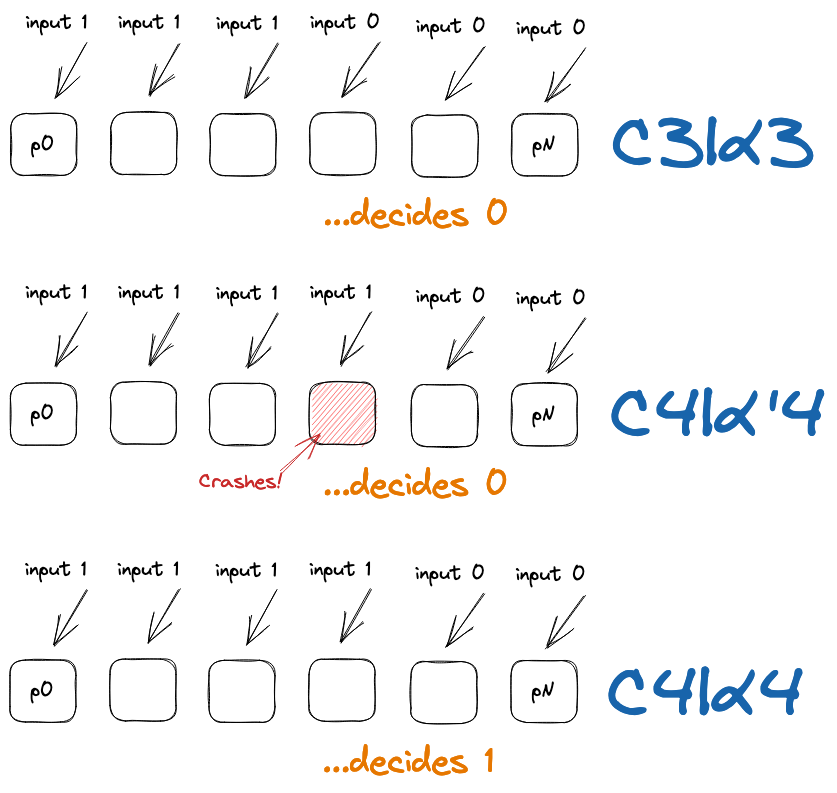

Define \(C_i\) to be the initial configuration (state) where processes \(p_0, …, p_i\) have input \(1\) and the others have input \(0\). Now, a valid consensus, for executions \(\alpha_0, … , \alpha_n\) starting from \(C_0, …, C_n\), where no processes fail, will return \(0\) starting from \(C_0\) and \(1\) starting from \(C_n\).

There must be some \(j\) where \(C_j, C_{j+1}\) decide different results.

Intuitively, an execution \(\alpha_{j+1}’\) starting from \(C_{j+1}\) where \(p_j\) crashes at the start is not distinguishable from \(\alpha_j\) following \(C_j\). \(\alpha_j\) and \(\alpha_{j+1}’\) must decide the same results which means that \(\alpha_{j+1}\) and \(\alpha_{j+1}’\) must decide different results even though they both start from \(C_j\).

b) Any \(f\) round execution is equivalent to one without crashes

Statement 2: any \(f\) round execution with \(f + 2 \leq n\) processes is equivalent to one without crashes.

The trick is as follows: in a round where a process \(p_i\) crashes, the crash may occur before \(p_i\) has had a chance to send all their outbound messages. If we suppose that \(p_i\) fails to send a message to \(p_j\), then there must be a live process \(p_k\) who cannot distinguish this execution from one where \(p_i\) did send a message to \(p_j\). We know \(p_k\) must exist because \(2 \leq n-f\). We can apply this to say that the execution where \(p_i\) crashes mid-round is indistinguishable from one where it crashes at the start of the next round.

This gives us an induction. We can move crashes in the \(f\)th round to the start of non-existent \((f+1)\)th round. Then, we can move crashes in the \(r\)th round to the \((r+1)\)th round and by induction eventually to the start of non-existent \((f+1)\)th round.